Polar decomposition

In mathematics, particularly in linear algebra and functional analysis, the polar decomposition of a matrix or linear operator is a factorization analogous to the polar form of a nonzero complex number z

where r is the absolute value of z (a positive real number), and  is called the complex sign of z.

is called the complex sign of z.

Contents |

Quaternion polar decomposition

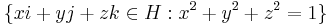

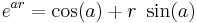

The polar decomposition of quaternions H depends on the sphere  of square roots of minus one. Given any r on this sphere, and an angle –π < a ≤ π, the versor

of square roots of minus one. Given any r on this sphere, and an angle –π < a ≤ π, the versor  is on the 3-sphere of H. For a = 0 and a = π , the versor is 1 or −1 regardless of which r is selected. The norm t of a quaternion q is the Euclidean distance from the origin to q. When a quaternion is not just a real number, then there is a unique polar decomposition

is on the 3-sphere of H. For a = 0 and a = π , the versor is 1 or −1 regardless of which r is selected. The norm t of a quaternion q is the Euclidean distance from the origin to q. When a quaternion is not just a real number, then there is a unique polar decomposition

Matrix polar decomposition

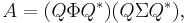

The polar decomposition of a square complex matrix A is a matrix decomposition of the form

where U is a unitary matrix and P is a positive-semidefinite Hermitian matrix. Intuitively, the polar decomposition separates A into a component that stretches the space along a set of orthogonal axes, represented by P, and a rotation represented by U. The decomposition of the complex conjugate of  is given by

is given by

.

.

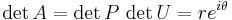

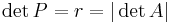

This decomposition always exists; and so long as A is invertible, it is unique, with P positive-definite. Note that

gives the corresponding polar decomposition of the determinant of A, since  and

and  .

.

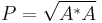

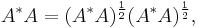

The matrix P is always unique, even if A is singular, and given by

where A* denotes the conjugate transpose of A. This expression is meaningful since a positive-semidefinite Hermitian matrix has a unique positive-semidefinite square root. If A is invertible, then the matrix U is given by

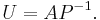

In terms of the singular value decomposition of A, A = W Σ V*, one has

confirming that P is positive-definite and U is unitary.

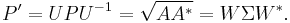

One can also decompose A in the form

Here U is the same as before and P′ is given by

This is known as the left polar decomposition, whereas the previous decomposition is known as the right polar decomposition. Left polar decomposition is also known as reverse polar decomposition.

The matrix A is normal if and only if P′ = P. Then UΣ = ΣU, and it is possible to diagonalise U with a unitary similarity matrix S that commutes with Σ, giving S U S* = Φ−1, where Φ is a diagonal unitary matrix of phases eiφ. Putting Q = V S*, one can then re-write the polar decomposition as

so A then thus also has a spectral decomposition

with complex eigenvalues such that ΛΛ* = Σ2 and a unitary matrix of complex eigenvectors Q.

The map from the general linear group GL(n,C) to the unitary group U(n) defined by mapping A onto its unitary piece U gives rise to a homotopy equivalence since the space of positive-definite matrices is contractible. In fact U(n) is a maximal compact subgroup of GL(n,C).

Bounded operators on Hilbert space

The polar decomposition of any bounded linear operator A between complex Hilbert spaces is a canonical factorization as the product of a partial isometry and a non-negative operator.

The polar decomposition for matrices generalizes as follows: if A is a bounded linear operator then there is a unique factorization of A as a product A = UP where U is a partial isometry, P is a non-negative self-adjoint operator and the initial space of U is the closure of the range of P.

The operator U must be weakened to a partial isometry, rather than unitary, because of the following issues. If A is the one-sided shift on l2(N), then |A| = {A*A}½ = I. So if A = U |A|, U must be A, which is not unitary.

The existence of a polar decomposition is a consequence of Douglas' lemma:

- Lemma If A, B are bounded operators on a Hilbert space H, and A*A ≤ B*B, then there exists a contraction C such that A = CB. Furthermore, C is unique if Ker(B*) ⊂ Ker(C).

The operator C can be defined by C(Bh) = Ah, extended by continuity to the closure of Ran(B), and by zero on the orthogonal complement to all of H. The lemma then follows since A*A ≤ B*B implies Ker(A) ⊂ Ker(B).

In particular. If A*A = B*B, then C is a partial isometry, which is unique if Ker(B*) ⊂ Ker(C). In general, for any bounded operator A,

where (A*A)½ is the unique positive square root of A*A given by the usual functional calculus. So by the lemma, we have

for some partial isometry U, which is unique if Ker(A*) ⊂ Ker(U). Take P to be (A*A)½ and one obtains the polar decomposition A = UP. Notice that an analogous argument can be used to show A = P'U' , where P' is positive and U' a partial isometry.

When H is finite dimensional, U can be extended to a unitary operator; this is not true in general (see example above). Alternatively, the polar decomposition can be shown using the operator version of singular value decomposition.

By property of the continuous functional calculus, |A| is in the C*-algebra generated by A. A similar but weaker statement holds for the partial isometry: U is in the von Neumann algebra generated by A. If A is invertible, the polar part U will be in the C*-algebra as well.

Unbounded operators

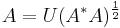

If A is a closed, densely defined unbounded operator between complex Hilbert spaces then it still has a (unique) polar decomposition

where |A| is a (possibly unbounded) non-negative self adjoint operator with the same domain as A, and U is a partial isometry vanishing on the orthogonal complement of the range Ran(|A|).

The proof uses the same lemma as above, which goes through for unbounded operators in general. If Dom(A*A) = Dom(B*B) and A*Ah = B*Bh for all h ∈ Dom(A*A), then there exists a partial isometry U such that A = UB. U is unique if Ran(B)⊥⊂ Ker(U). The operator A being closed and densely defined ensures that the operator A*A is self-adjoint (with dense domain) and therefore allows one to define (A*A)½. Applying the lemma gives polar decomposition.

If an unbounded operator A is affiliated to a von Neumann algebra M, and A = UP is its polar decomposition, then U is in M and so is the spectral projection of P, 1B(P), for any Borel set B in [0, ∞).

Alternative planar decompositions

In the Cartesian plane, alternative planar ring decompositions arise as follows:

- If x ≠ 0, z = x ( 1 + (y/x) ε) is a polar decomposition of a dual number z = x + y ε, where ε ε = 0. In this polar decomposition, the unit circle has been replaced by the line x = 1, the polar angle by the slope y/x, and the radius x is negative in the left half-plane.

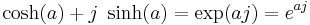

- If x2 ≠ y2, then the unit hyperbola x2 − y2 = 1 and its conjugate x2 − y2 = −1 can be used to form a polar decomposition based on the branch of the unit hyperbola through (1,0). This branch is parametrized by the hyperbolic angle a and is written

-

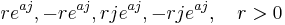

- where j j = +1 and the arithmetic of split-complex numbers is used. The branch through (−1,0) is traced by −ea j. Since the operation of multiplying by j reflects a point across the line y = x, the second hyperbola has branches traced by jea j or −jea j. Therefore a point in one of the quadrants has a polar decomposition in one of the forms:

- The set (1,−1,j,−j) has products that make it isomorphic to the Klein four-group. Evidently polar decomposition in this case involves an element from that group.

See also

References

- Conway, J.B.: A Course in Functional Analysis. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. New York: Springer 1990

- Douglas, R.G.: On Majorization, Factorization, and Range Inclusion of Operators on Hilbert Space. Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 17, 413-415 (1966)

- Sobczyk, G.(1995) "Hyperbolic Number Plane", College Mathematics Journal 26:268–80.